Interview with Mr. Sławomir Samardakiewicz

Date of the interview : 02.08.2021

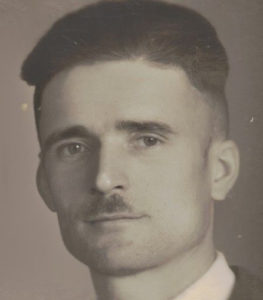

Sławomir Samardakiewicz

Professor in Adam Mickiewicz University, Faculty of Biology.

He has been married for 25 years with his wife Mirella.

Father of 21-year-old Ania and the late Kuba.

His hobbies are traveling and taking pictures of landscapes.

When he visited Japan on business in 2001, he happened to see a photo of

the Siberian Children and discovered his grandfather among them.

Thank you for your cooperation with this interview. We are very happy to hear your story online despite the pandemic situation.

Let me ask you the first question. Could you please tell us how you are related to the history of the Siberian Children?

My grandfather, Jan Samardakiewicz, was one of the Siberian Children. He was born in 1909 in Malinówka near Tomsk in Siberia. He had two younger siblings : Antoni (born in 1911) and Adela (born in 1914). Antoni traveled the entire route from Manchuria through Japan and the US to Poland with my grandfather. We know that Antoni lived in Warsaw at the end of the 1930s and worked as a shoemaker. Adela remained in Manchuria, although her later fate was also connected with Japan and the US. Around 1937, she married Walenty Kuczyński, a famous athlete and teacher in a junior high school in Harbin. Walenty later became a hero at the Siege of Tobruk and the Battle of Monte Cassino. The second husband of Adela was Ormond Gigli, a famous American photographer.

Both Antoni and Adela probably died childless. As for the descendants of my grandfather Jan, three of his six children are still alive today, including my mother Teresa. And of course, there are his grandchildren, great-grandchildren and even great-great-grandchildren.

It’s amazing how the fate of your family turned out and how persistent and mentally strong they must have been.

I should emphasize that the fate of the Siberian Children was full of traumatic experiences.

It is difficult for us to even imagine what the children who lost their families had to do to survive in the world of constant warfare, poverty, diseases, and terrible hunger.

Hence, most of the Siberian Children did not share their experiences from that period, even as adults. Sometimes their family did not find out anything about these events until their deathbeds, or even after their death.

What was the relationship between you and your grandfather like?

Have you had an opportunity to hear your grandfather’s history directly from him?

My grandfather was very secretive and reluctant to share his memories.

According to my mother, he spoke about individual events from that period sporadically during her childhood, adapting these stories to the children’s sensitivity.

I have met my grandfather only a few times in my life. Unfortunately we rarely visited each other as we lived several dozen kilometers apart.

When I was 16, I went to visit him alone. It was my first time spending a few hours with him and hearing his childhood experiences directly from him.

I clearly remember this conversation as if it was today, even though more than 35 years have passed since then (it was 1985).

First, he started talking about the terrible conditions, poverty and unimaginable hunger in Siberia, which was not a place for people to live.

He said that he often had to beg or steal to get food in order to survive.

When he was 10, he jumped over the fence surrounding the orchard to get some fruit for himself and his family. He then stumbled onto the barbed wire, which cut his skin on his stomach and arms. The owner of the orchard saved his life. The scars from this accident remained in his body for the rest of his life. Interestingly, my grandfather was a gardener and fruit grower.

My mother visited my grandfather’s homeland during her studies in the early 1970s to collect Polish dialect materials for her master’s thesis. Then she found out that her father helped young Poles from being deported to Nazi Germany for forced labor during World War II.

During the war, my grandfather was working in the gardens and orchards which were owned by Germans. Since he was a skilled gardener, as well as a very hardworking and honest man, he managed to obtain the owner’s consent to employ the Poles at risk of deportation.

That’s amazing. Did your grandfather tell you anything else?

Yes, he also told me about his passion for his work as a gardener. He liked to experiment in the garden, especially growing roses.

He also told me about his future plans. I promised then that I would be back soon and continue our talks.

One week later, however, I received the news that my grandfather passed away – it was really a bolt out of the blue. I became the last person in my family to hear my grandfather’s childhood story directly from him.

Only then I realized that he was physically exhausted when he was talking to me. But I wasn’t aware that it was a sign that he didn’t have much time left.

I would like to express my sincere condolences to your grandfather.

I am grateful that you managed to talk to your grandfather, so that his memory will not disappear.

Did you try to find or find out any information about the Siberian Children or your grandfather?

I would like to tell you the story of when I found the footprints of my grandfather in Japan.

Exactly 20 years ago, I was attending a conference in Nagoya.

Then I visited the Meiji-Mura museum nearby. There, while walking up the stairs in a building, I suddenly saw a huge picture on the wall in front of me. On a large passenger ship, a large crowd of children waved handkerchiefs. The children looked like Europeans.

When I read the description, I was suddenly confused.

They were the Siberian Children, and my grandfather must have been among them. I was then overwhelmed with emotion. The picture was a part of an exhibition about the Japanese Red Cross Society (JRCS). The Siberian Children rescue missions were the first international humanitarian aid project for the JRCS.

It must have been a special moment for you. Have you ever seen any pictures of your grandfather before?

Actually, I’ve seen my grandfather’s album a few times. The album included photos taken during his stay in Manchuria, but none were taken in Japan.

But thanks to you, I was able to see the first photo of my grandfather’s stay in Japan. In the picture, I could easily recognize which child was my grandfather.

His brother Antoni was in the picture next to him. (Jan and Antoni always stood together in group photos.)

It’s amazing that so many things were discovered by chance. We are very pleased that you managed to find new photos.

Could you explain why your grandfather was in Siberia? How did it happen that he joined the group of children who went to Japan?

The story of my grandfather and his siblings begins in Tomsk, a city in West Siberia, Russia.

Their parents were Aleksander Samardakiewicz and Emilia Samardakiewicz. Emilia was born into the Pawłowicz family in 1893 in Grauże, currently located in Belarus. We don’t know how Emilia ended up in Siberia, perhaps it was related to the forced exile of her family by the Russian Empire. From the deeply patriotic idea that Emilia instilled in her children, it may be related to the fact that many Poles were sent to Siberia by the Russian invader.

We know nothing about her husband Aleksander. We do know, however, that in 1920, Emilia was in Manchuria with her three children as a widow. During the civil war in Russia that began in 1917, many Poles recognized Manchuria, especially its capital, Harbin, as a place of refuge. There was a strong Polish community at that time in Harbin. In addition, few people know that Harbin, which currently has over 5 million inhabitants, was founded in 1898 (during the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway) by Adam Szydłowski, a Polish engineer.

I didn’t know that. Poles often appear in the pages of history at unexpected moments…!

Exactly. I think Emilia came to Harbin with a group of refugees from Siberia. My family has information that the typhus epidemic that broke out in Tomsk at that time was the reason for the evacuation. Emilia was put in a very difficult situation. She had to earn enough money to support her three children as a single parent. She worked as a housekeeper, but that wasn’t enough to survive. Hence, she was forced to give her children to an orphanage.

When the opportunity arose for the children to return to Poland, she must have felt as if her heart was bleeding. At the same time, however, she saw it as an opportunity for her children for a better tomorrow and a chance to return to their homeland.

Jan and Antoni were then in an orphanage near the Mulin station (about 300 km from Harbin), organized by the Polish Red Cross with the help of Stanisław Sokołowski. From there, they were transported to Vladivostok, and in mid-September 1920 they were transported by ship to Tsuruga Port, Japan. Emilia remained in Manchuria with the youngest child, Adela. I’d like to tell you Adela’s story in another interview because her life was extraordinary.

Certainly, her story is very intriguing and will be great material.

Do you know what the life of your grandfather and his brother looked like after they came to Japan?

My grandfather and his brother Antoni stayed in Japan only for a short time, from September to December 1920. In December, they left for the United States with other children. From the port of Seattle, they traveled to Chicago by train, where they were taken care of by the Polish community in the US. My grandfather attended junior high school there and acquired knowledge and skills in the field of gardening, which helped him out in the future.

We don’t know many details about their stay in the US. In his mementos from this period, we could find only the address of Louise Kasperek (maiden name: Uczciwek), who probably helped the Samardakiewicz brothers at that time.

It should be added here that Polish families in the US encouraged the Polish children to stay in the US. And indeed some of them remained. However, my grandfather and his brother were so determined to return to Poland that at the beginning of 1922 they set off with other children from New York to the ports of Bremen, the last stage of their journey to Poland. From Bremen, they traveled to Poznań by train.

I was inspired by young children’s strong desire to return to their home countries.

Yes, I always admire it. In Wielkopolski (the province where Poznań is located), charity organizations took care of the Siberian Children.

Unfortunately, as Professor Wiesław Theiss describes in his book, the children were often in dangerous situations. This led to the initiative to establish a special center for the Siberian Children in Wejherowo, but it was after my grandfather’s arrival in Poland from Japan.

My grandfather and his brother ended up in an orphanage in Broniszewice. We could not find any memories of my grandfather from there, other than a document written by the leader of the steward, who gave the opinion to my grandfather: “he behaved blamelessly, he was conscientious and honest.” From there he was directed by his legal guardian – Father Walenty Dymek, director of Caritas, who later became Archbishop of Poznań. There he practiced gardening with Edward Netzl, who was running a modern farm in Szeląg, Poznań. This is how Jan started his life as a gardener. Before World War II, he married my grandmother Jadwiga (maiden name: Nowak). They had six children, including my mother Teresa. In order to support such a large family, my grandparents worked very hard. At the same time, my grandfather was saving money to start his own gardening business in the future. Unfortunately, because of the denomination which was introduced by the communist authorities in 1950, he lost all his savings. He could no longer afford to buy his own farm. Therefore, he had to work on a state farm for a low wage, and his children had to work as well.

The Samardakiewicz family moved many times in Wielkopolski. In 1962, my grandmother Jadwiga died. My grandfather finally settled in Jerzykowo, near Poznań, from where he commuted to work in poznański Zakład Zieleni Miejskiej (Poznań Park Service) until his retirement. He often worked as a gardener at the Poznań International Fair as well. He told me that he had surprised delegations from China and Japan by speaking to them in Chinese and Japanese as an inconspicuous gardener. I must add here that my grandfather spoke beautiful Polish all his life. There was no influence from the accent of other languages that he learned in his childhood, such as Russian. Despite the strong pressure from the Russian authorities which aimed at denationalization of Poles in Siberia, he was not Russified. It is because his family had a patriotism for Poland.

It’s wonderful that what he learned as a child was useful to him even when he became an adult.

Are there any other episodes or memories from Japan that your grandfather remembered for a long time?

As I’ve already mentioned, he could speak Chinese and beginner-level Japanese. His stay in Japan was like “the Sunrise of Hope”’ for him if I use a phrase from a Japanese poem. I think it was one of the brightest times in his life. At the same time, however, please remember that he left his mother and his beloved sister across the Sea of Japan. In addition, my grandfather, then a 11-year-old boy, was responsible for his younger brother. On top of this, he must have been very anxious about what would happen to them next.

One of his mementos from his stay in Japan is a postcard with the signature of Takao Atsumi. Next to the signature, there is a note “24 years old”. I guess it might have been one of the carers of the Fukudenkai Center who was very nice to my grandfather. I think Takao Atsumi was so important to my grandfather that this postcard remained with him all his life. I am grateful that Fukudenkai is now searching for the descendants of the Siberian Children. I hope that one day I’ll find traces of Takao Atsumi.

We sincerely hope that there will be new discoveries about their fate.

May I ask where your great motivation to gather information about your family comes from?

For me and other families of the Siberian Children, it is like a mission so that they and their memories would not be lost. I also keep in mind that we should not lose the memory of all the people and institutions like Fukudenkai that helped these children in a spirit of mutual aid.

Researching and talking about the history of 100 years ago is a form of gratitude to the people who helped the Polish children. We should also keep in mind that if it were not for them, we would not be talking to each other today.

Fukudenkai also wishes to spread the history of the Siberian Children and its related information in order to keep their memories alive.

However this is not always a happy story. What are your feelings about telling such a private story to others?

For the Siberian Children, the journey must have been a traumatic and unforgettable experience.

We, their descendants, are not directly burdened with such experiences, so we can speak about it for them. In this way, we can spread the history, and at the same time, it is an opportunity to deal with the trauma of our ancestors.

Yes, it is very important to help complete issues that the Siberian Children were not able to finalize themselves.

Do you know anyone who also knows this history other than your family?

In telling various people about the story of my grandfather’s fate, only one listener knew the story of the Siberian Children. He was a Polish missionary who had lived in Japan for more than 30 years. When I met him in 2020, he told me that this story was well known in Japan because Japanese children had the opportunity to learn about it in schools. I don’t know if it is actually widely introduced in schools all over Japan, but it touched me a lot then. That is because I know that Polish children learn in history classes, for example about internal customs during the Civil War in North America, but they do not know the fate of Poles fleeing Siberia. As for the painful fate of Polish children in Siberia, the deportation of Poles to Siberia by the Soviet Union during World War II, is better known in Poland. Some of these children are still alive today.

In addition to the history of deportation of Poles to Siberia, it is worth mentioning Japan’s humanitarian aid for the Siberian Children in the 1920s. 20 years later, in 1941, almost 5000 Polish children from Siberia found shelter in India thanks to a kind-hearted king, Maharaja Digvijaysinhji.

The history of the Siberian Children appeared in school programs before World War II thanks to a short story entitled “Brothers (Original title: Bracia)” by a famous Polish writer Zofia Nałkowska. After the war, however, this topic was not mentioned because it was inconvenient for the Communist authorities in Poland. This may also explain why the Siberian Children were so reluctant to share their experiences. Now, however, there is nothing to prevent us from talking about this topic, people in Poland talk more often about it.

We hope that more young people will be interested in this topic.

Do you think the history of the Siberian Children should be better known among Japanese and Poles?

The Roman writer and philosopher Cicero wrote over 2,000 years ago:

“Historia magistra vitae est (History is the teacher of life)”.

I think there is a similar approach to history in Japan because it allows us to learn from the mistakes of the past and avoid making the same mistake again. Naturally, young people keep their eyes on the future, and sometimes reject learning history. This is wrong. I think it is easier to reach them when they are told about history based on the fate of their peers. Hence, I think it is worth introducing the history of the Siberian Children to young people.

In addition to the school education, what other activities do you think could contribute to hand the story down to the next generation?

I think education for children at school is necessary – not only through information in textbooks, but also through face-to-face meetings at schools with the descendants, historians or people dealing with this subject.

For me, important sources of information are books, scientific publications and memoirs of the people involved. I especially appreciate the extremely comprehensive study by prof. Wiesław Theiss “The Siberian Children 1919 – 2019. From Siberia to Poland via Japan and the United States (Original title: Dzieci Syberyjskie 1919-2019. Z Syberii przez Japonię i Stany Zjednoczone do Polski)”, published in 2020 by Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology.

Another important element of education is museum exhibition. However, sometimes it is difficult for busy people to visit museums. For this reason, museums sometimes organize open-air exhibitions these days. So I really like the idea of the panel exhibition which was organized by Fukudenkai in Krakow in 2021. In this way, this information reaches passersby directly and randomly. A chance encounter with this history can inspire or shake their hearts.

Today, the Internet is often the main source of information for people. I myself have managed to find important information about the life of my grandfather and his siblings on the Internet. Let me give you an example. After the war, my grandfather was looking for his siblings. Unfortunately, the only information he got was that they were both missing. However, in 2021, after over 70 years of searching by my family, I accidentally found out on the Internet that Adela survived the war. She lived in Japan throughout the war, and in 1946 she left Yokohama for the US, where she spent the rest of her life. In 1951 she remarried, and the following year she acquired American citizenship and from then she started calling herself Janine Gigli. Unfortunately, we do not know her further fate, but it seems that she traveled to Europe several times in the 1950s as her name was listed on the passenger lists of ships. I’ll talk about this in the next interview. Maybe someone who knows her would read this interview and share information about her with us. I also hope so in the case of Antoni Samardakiewicz. Unfortunately, there are fewer and fewer witnesses who could know these people.

I am amazed at how much we can learn from all the information on the Internet.

Exactly. Therefore, it is important to post information about the Siberian Children on the Internet. This is what your organization also does through the website siberianchildren.pl, in cooperation with ASAGAO. I am glad that there are also films on this subject that can be watched on the Internet. Recently, a documentary film “Andzia – A journey of a girl (Original title: Andzia – historia jednej podróży)” was released by The Krotochwile Association (Stowarzyszenie Krotochwile). I know that the authors are also preparing an English version and a version for schools. I think that is a very good idea.

We are very pleased that our website has reached you and today we have the opportunity to share our knowledge.

There are various ways to let more people know about the history, but among them, the best living evidence of those events is the connection of those who are alive today.

I am convinced that the ceremony in 2022 will certainly be extremely valuable both for Poles and Japanese, as well as for other participants of this event. It is important to create platforms for this type of meeting. I am also glad that there are platforms for student exchange activities, such as the Japan-Poland Youth Association.

We are making every effort to ensure the best possible integration of the young generation from both countries.

I hope for the best possible relations between Poland and Japan.

I was also very touched by the activities of the Football World Cup for children in orphanages organized by Hope for Mundial(Nadzieja na Mundial. I know that young footballers from Poland and Japan also participated in this competition.

I hope this competition will resume and continue after the pandemic is over. Sports competition brings people closer. We just experienced it during the Olympic Games in Tokyo. I was supporting the Polish volleyball team. The Japanese team lost the match against the Poles, but I was impressed with their bravery and excellent preparation for the match.

I also enjoyed watching the volleyball match and it was very nice.

It would be great if events related to Poland and Japan are held every year. In 2021, the Olympic Games were held in Tokyo, and in 2022, the Ceremony to commemorate the centenary of the arrival of Siberian Children in Japan will be held in Warsaw.

Do you have any ideas about this ceremony organized by Fukudenkai?

I know that this ceremony has already been postponed twice due to the epidemic. There is a proverb in Poland “do trzech razy sztuka (Third time lucky)”. Often good works encounter great difficulties at first. So it seems to me, paradoxically, this is a good sign. I am glad that Fukudenkai is organizing such a ceremony and I believe that it will result not only in a better understanding of this history, but also in further strengthening of relations between Poland and Japan.

I hope so too. Would you be interested in attending events other than the ceremony, such as small meetings of the families of the Siberian Children?

Yes, I am looking forward to this type of meeting. I hope to make new acquaintances and expand my knowledge. On the other hand, of course, I would like to share with others what I have learned about the fate of my grandfather and his siblings.

Thank you very much for your time today. Before we finish, is there anything you would like to add?

At the end of this interview, I would like to tell you about my visit to the Yad Vashem Museum in Israel. There is a special monument there dedicated to Jewish children murdered during World War II. The building was funded by the parents of Uziel, a 2.5-year-old boy, who murdered during the war. When you step inside, you see endless darkness illuminated by the light of an infinite number of candles. However, it is an optical illusion. In fact, there is only one candle, and its glow is multiplied by the reflection in the numerous mirrors. This represents the descendants of Uziel that would have prospered if he had survived. This alludes to a famous statement in the Talmud that “Whoever Saves One Life, Saves the World Entire.”

People in Japan may not realize how many people in the world they saved 100 years ago, including my World – family. I thank you with all my heart.

Thank you very much for today!